How to Talk About Money in the Art Field

Airi Triisberg

Money is an inconvenient topic in the art field. We don’t hear much about it, apart from bitter declarations that there is not enough. What kind of communication protocols and standards are needed in order to improve working conditions?

The general silence about money has unfortunate consequences: there are no widely accepted standards for negotiating payment. Curators might feel uneasy to admit that they do not have sufficient funds to remunerate the work of artists fairly. Artists might feel too insecure to address monetary questions, because there is no proper social protocol for discussing payment. It is not exceptional for a cooperation between artists and curators to develop without addressing the issue of pay at all.

The conversation about payment is also complicated because there is no consensus about defining art as work. For many artists, their practice is by definition different from wage labour. Furthermore, art is not always made for the sake of money. Making art is more often driven by non-monetary motivations: intellectual, spiritual, critical, etc. The value systems affiliated to art are usually non-financial, and therefore, talking about money can be considered mundane or even vulgar. Many art workers can tell anecdotes about awkward situations. I myself have earned a number of sniffy nicknames while campaigning against precarious work in the art sector, including, for instance, "material girl". (Others are accused of "unacceptable" behaviour, merely for touching upon the big issue at the wrong place, or wrong time.)

During the lockdowns resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, exhibition spaces and cultural institutions were abruptly closed, their programmes cancelled, postponed, or installed in empty venues. The pandemic revealed a vulnerable spot in the art sector: the lack of standard contracts and work agreements. In the face of unexpected circumstances, many art practitioners were confronted with difficult questions: Were our agreements made formally or casually, verbally or in writing? Were the terms and conditions negotiated in detail? Are the agreements binding?

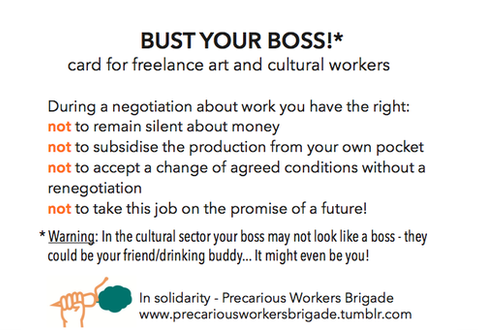

Nevertheless, the conversation about working conditions in the field is not new. Precarious working conditions were discussed with particular intensity 2008-2012. Numerous self-organised art workers’ collectives emerged during those years, in different locations, working collectively against unpaid and underpaid labour, or demanding access to basic social guarantees, such as health insurance. One visual relic of that cycle of struggle is the Bust Your Boss Card developed in 2011, by the London- based group Precarious Workers Brigade: an awareness-raising visual tool that encourages cultural workers to confront their "bosses" by demanding more transparency. The card borrows the format of the "bust card" that is usually handed out at protests, giving legal information to activists and demonstrators. Isn't it striking that this card was produced a decade ago, but has not lost any actuality or accuracy? Building on the spirit of the Precarious Workers Brigade, I would like to make a few additions to the card in question.

When is the right time to talk about money?

Although the issue of money might feel like an embarrassing or explosive topic, it should be completely normal to address it at the very beginning of a work relation. Nor should this initial conversation be limited to payment. It is also important to clarify expectations, distribute responsibilities, fix time schedules, specify juridical details and applicable taxes, and discuss all other relevant matters in relation to working conditions.

Relations between freelance art workers and art institutions are not typical relations of wage employment. In rare cases, they’re regulated through short-term or part-time work contracts. More often, the work relations are hidden behind licence agreements, purchases of services, stipends, etc. It is important to understand that these descriptions amount to a semi-formal façade, behind which art workers are routinely being employed to perform their jobs. In order to keep this power relation visible, I am using the terms "employer" and "employee" to signify the two parties in a temporary work relationship. Employer refers to the party which commissions the work: be it an art institution, self-organised project space, independent curator or a fellow artist. Employee refers to the independent art worker who performs the job, independently from their legal status, which could be self-employed artist, sole proprietor, entrepreneur, company, or none of the above.

Don't be shy about money! Start talking about working conditions from the moment the working relationship is initiated.

How much money do I actually get?

When negotiating payment, please specify which taxes will apply to the agreed amount. A frequent source of miscommunication is when employers talk in gross amounts, while employees hear the net amounts. For example, when a payment of 100 euros is discussed in Estonia, it all depends on the legal form of the agreement: the net amount can be 100, 80 or 58 Euro, all depending. Regulations vary in different countries, so don't forget to discuss the taxes, they can make a substantial difference in your net payment.

Which contract do we sign?

In the context of international collaborations, the employer is often in a privileged position, in terms of knowledge of the local tax system, or other juridical aspects of the contract. Sometimes they need to be reminded of the responsibility to transmit that information to their cooperation partners. On the other hand, there are plenty of employers in the art field whose juridical and financial knowledge is extremely weak. On once occasion, the employer started researching tax obligations two months after I had performed my work. The payment was accordingly stalled. This employer was not an independent curator, or a self-organised collective, but a newly established and wealthy biennial.

Ask your employer to explain the choice of contract they are proposing. Why do they prefer this particular contract type when there are other options? What are the advantages and disadvantages of different contract types, including licence agreements, temporary work contracts, grant agreements, sales agreements, etc.? How do different contracts influence access to social security?

When will we sign the contract?

When I think back to my own experience as an independent art worker, it strikes me that the moment when the employer finally sends me the contract is almost always the same: when I have performed and submitted my work, but the payment has not been transferred yet. What are the chances that such timing is coincidental? There have been situations when I did not agree with the terms presented in the contract, but how to start negotiations at this stage? What if this conversation ends with conflict, and I risk losing payment for the work that I have already done?

Don't wait until the contract is belatedly presented to you by the employer. You have the right to read it before you start performing your job.

And by the way. A contract is valid when both parties have signed it. It is very common that the employer collects the signature of the employee, archives it for the sake of "obligatory formality", but the employee does not receive a signed copy in turn. Do not hesitate to ask for a signed contract!

"But wait a minute, we never talked about this!"

In my experience as frequent public speaker, the most typical hidden clause in the contract is about recording, streaming or online distribution of talks and seminars. Such intentions very often remain unmentioned in the initial email correspondence, when dates, content and payment are discussed. I usually discover it when the contract is handed to me last minute, or when the technical assistant approaches me to attach the microphone to my shirt. "But hang on, I never agreed to this!"

If you prefer to say 'no' to unexpected tasks, don't let yourself be pressured by the urgency of the situation. Take a moment to sit down with your employer and talk things over. You do not have to agree to the surprise clauses in the contract. It should have been the responsibility of the employer to ask for your consent from the very start.

Sometimes, I fail to follow this advice myself, petrified as I read the four-page standard contract presented by some Western art institution. Such a detailed contract usually gives evidence of a professionalised approach to legal matters. On top of generating pressure through a time deficit, it overwhelms you with the exuberance of information. My response is usually resignation. What would be the point of entering into a dispute with the legal team of an entire institution? Is it worth wasting my time on this?

It took me a while to understand that the details of institutional standard contracts can also be negotiated. Most art institutions are open to changing or specifying a clause or two. They will not present this option to you on their own initiative, but will be cooperative when you insist.

You always have the right to negotiate. Don't hesitate to make use of it!

Do I have to become an entrepreneur to work in the art sector?

The hegemony of the neoliberal economic paradigm reflects upon the art sector too. Instead of signing contracts and paying wages, it has become common to settle accounts by purchasing services and exchanging invoices. The misunderstandings over net payment are often connected to the assumption that the independent art worker will present an invoice. However, in many countries, the legal status of "self-employed artist" does not exist, and some art workers choose not to become entrepreneurs, sole proprietors or companies.

Don't let yourself be pressured into believing that you are less professional because you do not act as a legal person. Legally speaking, you have every right to work in the art sector as a physical person.

When will you answer my question about finances?

In 2020, I was working with three art institutions. And I remember three different occasions when I raised questions about finances: in two cases, I repeated my question three times until I received an answer – two months later – while in the third case, the deadline for publishing this text arrived before the answer did. (There was also a fourth scenario; I was informed early enough that the institution was going to be slow, which spared me the trouble of futile correspondence from the outset.) The questions I asked were not very complicated, but did not lie comfortably within our prior financial agreements. In comparison, when I asked questions that did not transgress the boundaries of prior agreements, I received swift responses. My lesson from this experience is to pre-emptively agree on communication protocol. Reluctance to deal with questions demanding non-standard solutions is standard institutional behaviour. Don't let it catch you by surprise!

Other standard patterns of institutional behaviour include defensive strategies. When an art institution is reluctant to acknowledge miscommunication from their side, they will call it a "misunderstanding". This will shift the responsibility towards you. Another golden classic is: "We did not reduce your fee, we raised your production budget!" Apropos, dear colleague, if you recognise yourself in this paragraph, then please know that I am not referring to what happened between me and you personally, but to what happens between independent art workers and institutions generally.

Will I risk my social welfare support when accepting your 50, 100 or 250 euros?

Among art institutions and other employers, it is common to believe that independent art workers are free agents on the labour market, perhaps even entrepreneurs. The reality is somewhat different. When payments circulating within the art sector are too small to guarantee decent living standards, independent art workers frequently rely on various instruments of state support. My own constant concern is related to health insurance. Sometimes, my only possibility to have coverage is through registered unemployment. However, being unemployed is a stigmatised position in the competitive art world, which assigns high status to permanent visibility, productiveness, international rotation, etc. (Complaints about "too much work" are a more popular small-talk topic than even bad weather.)

Not every country offers unemployment benefits, and regulations differ in each context. However, if you do have access to support, you might be confronted with the following dilemma: "Should I accept this short-time gig, that does not pay much, but gives me much needed visibility, or should I say no, in order to continue receiving state support?" Don’t be afraid to discuss this with your friends, colleagues and employers. Social welfare must not be a stigma!

In case you are in the role of an employer, don't assume every independent art workers is a sovereign agent in the labour market. Ask your cooperation partner whether the income you are offering would be in conflict with conditions of state support that they might be receiving. The less you pay, the more considerate you should be!

Please visit the homepage of the SPK to find out more about Airi Triisberg and her work.